Ballastexistenzen es el término, ideado por el medico alemán Alfred Hoche en los años 20 del siglo pasado, que servía para definir aquellas vidas que eran consideradas indignas e inútiles para el estado y que validaba, desde el punto de vista moral, la eutanasia y los procesos de esterilización.

El régimen nacionalsocialista sustituyó el término Ballastexistenzen y otras acepciones de origen médico por “asocial”, que englobaba a personas de colectivos marginados: ladrones de poca monta, mendigos, alcohólicos, prostitutas y todos aquellos que no encajaban en el ideario de la Volksgemeinschaft o comunidad del pueblo.

Los "asociales" fueron los primeros, junto a los presos políticos, en ser aislados en régimen de custodia preventiva en los llamados campos de concentración.

Sachsenhausen fue un campo inaugurado en verano de 1936 en la localidad de Oranienburg, a treinta kilómetros de Berlín. El arquitecto Bernhard Kuiper diseñó un recinto panóptico -con planta en forma de triangulo equilátero- que debía servir como modelo para el resto de los campos.

En 1938 se produjeron los primeros fallecimientos en masa de prisioneros, el 80 por ciento pertenecía al grupo "asocial".

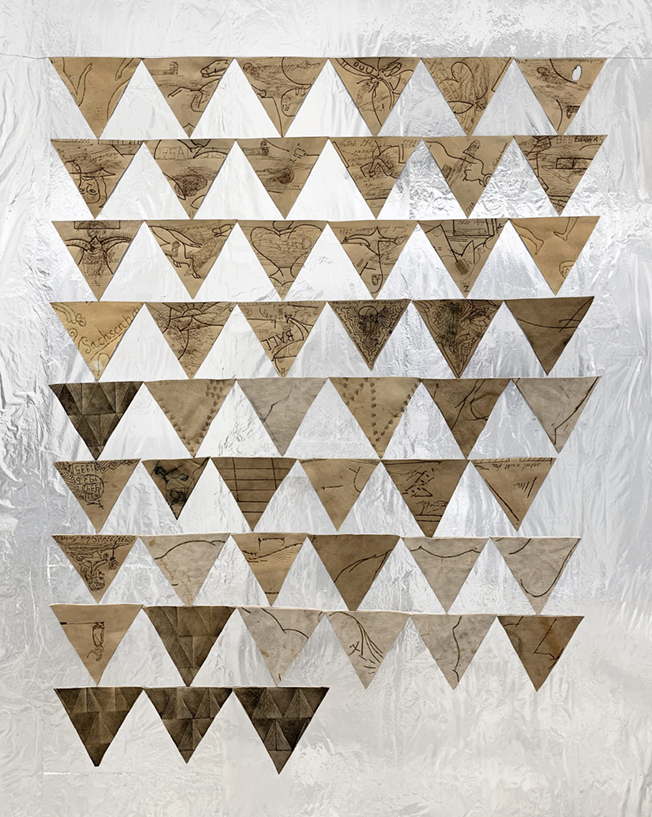

Felipe Talo comienza a investigar y guiar en el Memorial de Sachsenhausen en 2013. Desde entonces se interesa por este grupo históricamente estigmatizado, que aún hoy perpetúa su condición invisible al no tener un memorial propio y que lo reconozca como un colectivo víctima del nazismo. La palabra estigma, de origen griego, se refiere a una marca hecha en el cuerpo con un hierro candente como señal de esclavitud o de infamia. Este concepto, en la cultura europea, está en los orígenes de una forma de iconografía subversiva: el tatuaje. En 1940, Erich Wagner, un joven médico de las SS, fotografió a 800 presos tatuados del campo de concentración de Buchenwald para su tesis, titulada Ein Beitrag zur Tatöwieringsfrage. Esta pretendía servir como estadística para el estudio del ideario criminológico de su tiempo, que vinculaba el tatuaje con seres biológicamente degenerados. Al terminar la guerra, Gustav Wegerer, prisionero e ingeniero químico ayudante de Wagner, declaró que los tatuados eran eliminados tras ser entrevistados y fotografiados. Wagner, en contra de su voluntad, nos deja un documento en el cual recoge una memoria invisible, frágil y quebradiza. Diseños ornamentales y simbólicos que nos interpelan desde el pasado sobre la naturaleza de las malas formas.

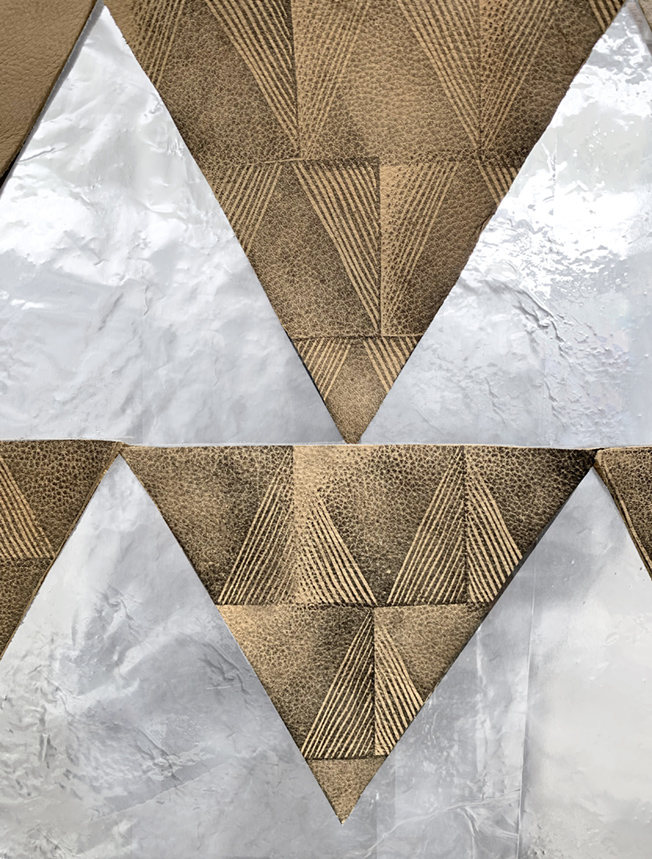

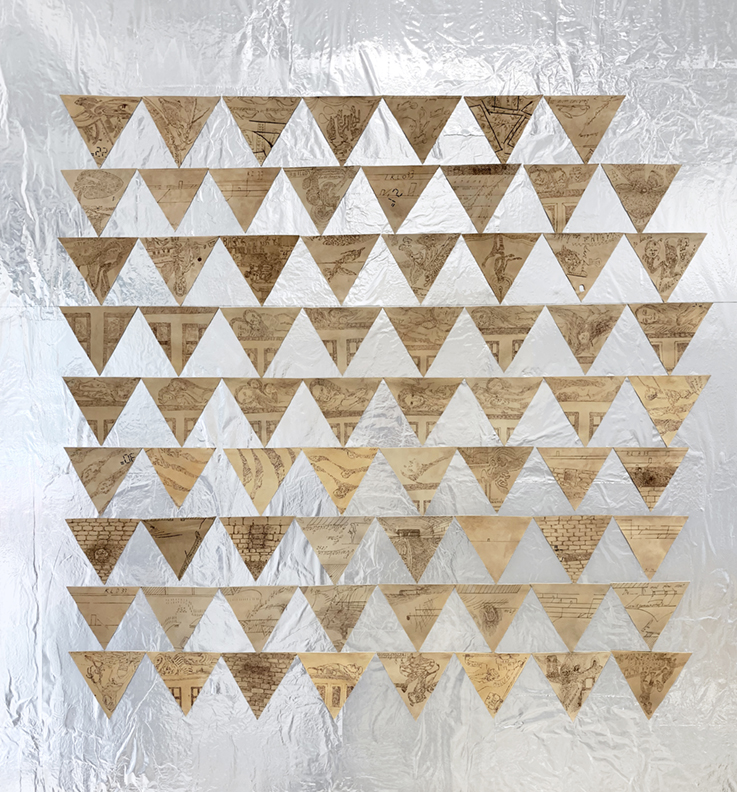

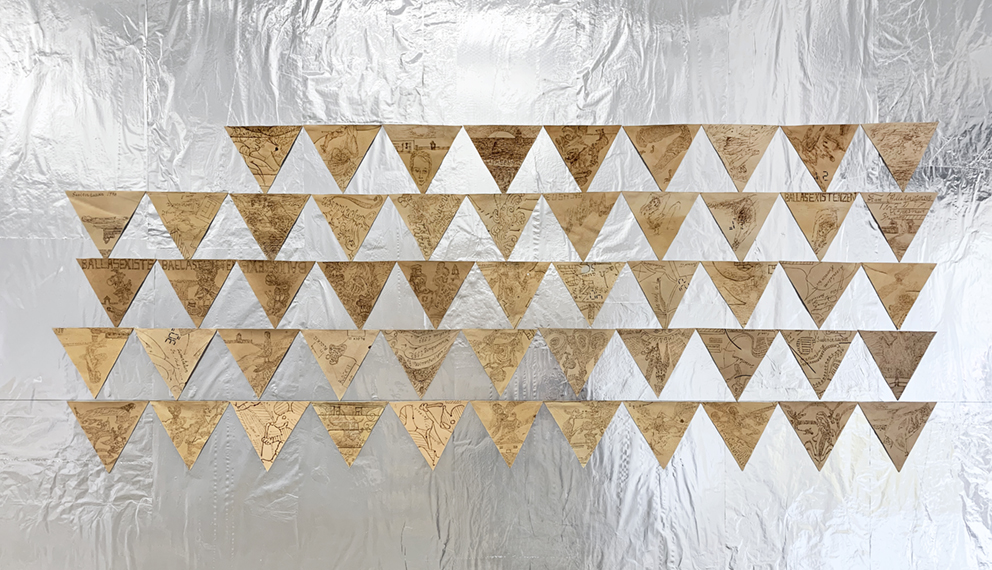

Talo propone una instalación donde los materiales crean una tensión de principios opuestos: pureza/deshecho, razón/caos, número y piel. El diseño triangular de Sachsenhausen es invertido por Talo, para contarnos la historia de estas Ballastexistenzen, subvirtiendo las formas de la represión, con piel, tinta y hierro candente.

Felipe Talo comienza a investigar y guiar en el Memorial de Sachsenhausen en 2013. Desde entonces se interesa por este grupo históricamente estigmatizado, que aún hoy perpetúa su condición invisible al no tener un memorial propio y que lo reconozca como un colectivo víctima del nazismo. La palabra estigma, de origen griego, se refiere a una marca hecha en el cuerpo con un hierro candente como señal de esclavitud o de infamia. Este concepto, en la cultura europea, está en los orígenes de una forma de iconografía subversiva: el tatuaje. En 1940, Erich Wagner, un joven médico de las SS, fotografió a 800 presos tatuados del campo de concentración de Buchenwald para su tesis, titulada Ein Beitrag zur Tatöwieringsfrage. Esta pretendía servir como estadística para el estudio del ideario criminológico de su tiempo, que vinculaba el tatuaje con seres biológicamente degenerados. Al terminar la guerra, Gustav Wegerer, prisionero e ingeniero químico ayudante de Wagner, declaró que los tatuados eran eliminados tras ser entrevistados y fotografiados. Wagner, en contra de su voluntad, nos deja un documento en el cual recoge una memoria invisible, frágil y quebradiza. Diseños ornamentales y simbólicos que nos interpelan desde el pasado sobre la naturaleza de las malas formas.

Talo propone una instalación donde los materiales crean una tensión de principios opuestos: pureza/deshecho, razón/caos, número y piel. El diseño triangular de Sachsenhausen es invertido por Talo, para contarnos la historia de estas Ballastexistenzen, subvirtiendo las formas de la represión, con piel, tinta y hierro candente.

Ballastexistenzen is the term, devised by the German physician Alfred Hoche in the 1920s, which was used to define those lives that were considered unworthy and useless to the state and which morally validated euthanasia and sterilisation processes.

The National Socialist regime replaced the term Ballastexistenzen and other medical terms with "asocial", which encompassed people from marginalised groups: petty thieves, beggars, alcoholics, prostitutes and all those who did not fit into the ideology of the Volksgemeinschaft or people's community.

The "asocials" were the first, along with political prisoners, to be isolated in protective custody in the so-called concentration camps.

Sachsenhausen was a camp opened in the summer of 1936 in Oranienburg, thirty kilometres from Berlin. The architect Bernhard Kuiper designed a panopticon compound in the shape of an equilateral triangle, which was to serve as a model for the rest of the camps.

In 1938, the first mass deaths of prisoners occurred, 80 percent of whom belonged to the "asocial" group.

Felipe Talo began researching and guiding at the Sachsenhausen Memorial in 2013. Since then, he has been interested in this historically stigmatised group, which even today perpetuates its invisible condition by not having its own memorial that recognises it as a collective victim of Nazism. The word stigma, of Greek origin, refers to a mark made on the body with a hot iron as a sign of slavery or infamy. This concept, in European culture, is at the origin of a form of subversive iconography: the tattoo.

In 1940, Erich Wagner, a young SS doctor, photographed 800 tattooed prisoners in the Buchenwald concentration camp for his thesis, entitled Ein Beitrag zur Tatöwieringsfrage. This was intended to serve as statistics for the study of the criminological ideology of his time, which linked tattooing with biologically degenerate beings. At the end of the war, Gustav Wegerer, a prisoner and chemical engineer and Wagner's assistant, declared that tattooed people were eliminated after being interviewed and photographed.

Wagner, against his will, leaves us a document in which he collects an invisible, fragile and fragile memory. Ornamental and symbolic designs that question us from the past about the nature of bad forms.

Talo proposes an installation where the materials create a tension of opposing principles: purity/waste, reason/chaos, number and skin. The triangular design of Sachsenhausen is inverted by Talo, to tell us the story of these Ballastexistenzen, subverting the forms of repression, with skin, ink and hot iron.

Felipe Talo began researching and guiding at the Sachsenhausen Memorial in 2013. Since then, he has been interested in this historically stigmatised group, which even today perpetuates its invisible condition by not having its own memorial that recognises it as a collective victim of Nazism. The word stigma, of Greek origin, refers to a mark made on the body with a hot iron as a sign of slavery or infamy. This concept, in European culture, is at the origin of a form of subversive iconography: the tattoo.

In 1940, Erich Wagner, a young SS doctor, photographed 800 tattooed prisoners in the Buchenwald concentration camp for his thesis, entitled Ein Beitrag zur Tatöwieringsfrage. This was intended to serve as statistics for the study of the criminological ideology of his time, which linked tattooing with biologically degenerate beings. At the end of the war, Gustav Wegerer, a prisoner and chemical engineer and Wagner's assistant, declared that tattooed people were eliminated after being interviewed and photographed.

Wagner, against his will, leaves us a document in which he collects an invisible, fragile and fragile memory. Ornamental and symbolic designs that question us from the past about the nature of bad forms.

Talo proposes an installation where the materials create a tension of opposing principles: purity/waste, reason/chaos, number and skin. The triangular design of Sachsenhausen is inverted by Talo, to tell us the story of these Ballastexistenzen, subverting the forms of repression, with skin, ink and hot iron.

Felipe Talo (Barcelona 1979) estudia Filosofía y Bellas Artes en la Universidad de Barcelona, así como mosaico en la Universidad de Ravenna (Italia). Vive en Berlín.

Del 2007 al 2009 trabaja junto a Nuria Fuster y realizan diferentes exposiciones individuales como Circuitos 2007, Generaciones 2008 y Explum 2008 y 2009. En el año 2008 desarrolla junto con Nuria Fuster, Antonio Lozano y Pablo Valbuena el proyecto HAMBRE que recibe las ayudas a la creación de Matadero Madrid en 2011 y que llega a celebrar hasta tres ediciones.

Realiza varias exposiciones individuales de las que destaca METEMPSICOSIS: WOMAN WITH BLUE BALL, en Blanco Projektraum Berlín 2013, LA LEYENDA NEGRA en Galería Alegría 2014, LOS EXTREMEÑOS Fundación Arranz-Bravo, Barcelona 2016, HIPNOSIS, Ribot Gallery (Milán) 2016, CONFESIONES DE UN AMANTE EXTREMO en Galería Alegría 2018 y BALLASTEXISTENZEN, Galería Picnic 2023.

Participa en diferentes proyectos y exposiciones colectivas como Casa Leibniz 2015 (Galería Alegría) en Madrid, Estampa 2015 (Galería Alegría) , Cuestión de Fe/Cuestión de trozo, junto a Lucía C. Pino, Martín Llavaneras y David Bestúe en el Centro del Carmen de Valencia en 2019, JUMPING AT GLEASONS junto al artista vienés Bernhard Rappold, 89CM UNDERGROUND con Kiko Pérez en 2022, ORNAMENTO Y DELITO conferencia y performance en la Sala de Anatomía de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid e instalación en Künstlerhaus Bethanien junto a Pilar Soler Montes (2023) o la más reciente, en Noviembre de 2023, SELF SUPER & HART AND KIND FOR ERIBODI en Krinzinger Galerie. Durante el año 2024 Felipe Talo desarrolla en tres capítulos el proyecto comisariado por Pilar Soler Montes, CUERDA Y CORAZÓN, del cual el primer capítulo ELOEM se inauguró en NADIE NUNCA NADA NO en enero de 2024.

Del 2007 al 2009 trabaja junto a Nuria Fuster y realizan diferentes exposiciones individuales como Circuitos 2007, Generaciones 2008 y Explum 2008 y 2009. En el año 2008 desarrolla junto con Nuria Fuster, Antonio Lozano y Pablo Valbuena el proyecto HAMBRE que recibe las ayudas a la creación de Matadero Madrid en 2011 y que llega a celebrar hasta tres ediciones.

Realiza varias exposiciones individuales de las que destaca METEMPSICOSIS: WOMAN WITH BLUE BALL, en Blanco Projektraum Berlín 2013, LA LEYENDA NEGRA en Galería Alegría 2014, LOS EXTREMEÑOS Fundación Arranz-Bravo, Barcelona 2016, HIPNOSIS, Ribot Gallery (Milán) 2016, CONFESIONES DE UN AMANTE EXTREMO en Galería Alegría 2018 y BALLASTEXISTENZEN, Galería Picnic 2023.

Participa en diferentes proyectos y exposiciones colectivas como Casa Leibniz 2015 (Galería Alegría) en Madrid, Estampa 2015 (Galería Alegría) , Cuestión de Fe/Cuestión de trozo, junto a Lucía C. Pino, Martín Llavaneras y David Bestúe en el Centro del Carmen de Valencia en 2019, JUMPING AT GLEASONS junto al artista vienés Bernhard Rappold, 89CM UNDERGROUND con Kiko Pérez en 2022, ORNAMENTO Y DELITO conferencia y performance en la Sala de Anatomía de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid e instalación en Künstlerhaus Bethanien junto a Pilar Soler Montes (2023) o la más reciente, en Noviembre de 2023, SELF SUPER & HART AND KIND FOR ERIBODI en Krinzinger Galerie. Durante el año 2024 Felipe Talo desarrolla en tres capítulos el proyecto comisariado por Pilar Soler Montes, CUERDA Y CORAZÓN, del cual el primer capítulo ELOEM se inauguró en NADIE NUNCA NADA NO en enero de 2024.

Felipe Talo (Barcelona 1979) studied Philosophy and Fine Arts at the University of Barcelona, as well as Mosaic at the University of Ravenna (Italy). He lives in Berlin.

From 2007 to 2009 he worked with Nuria Fuster and held various solo exhibitions such as Circuitos 2007, Generaciones 2008 and Explum 2008 and 2009. In 2008, together with Nuria Fuster, Antonio Lozano and Pablo Valbuena, he developed the project HAMBRE (HUNGER), which was awarded the Matadero Madrid Creation Grants in 2011 and went on to hold three editions.

He has held several solo exhibitions of which METEMPSICOSIS: WOMAN WITH BLUE BALL, in Blanco Projektraum Berlin 2013, LA LEYENDA NEGRA at Galería Alegría 2014, LOS EXTREMEÑOS Fundación Arranz-Bravo, Barcelona 2016, HIPNOSIS, Ribot Gallery (Milan) 2016, CONFESIONES DE UN AMANTE EXTREMO at Galería Alegría 2018 and BALLASTEXISTENZEN, Galería Picnic 2023.

He participates in different projects and group exhibitions such as Casa Leibniz 2015 (Alegría Gallery) in Madrid, Estampa 2015 (Alegría Gallery) , Cuestión de Fe/Cuestión de trozo, together with Lucía C. Pino, Martín Llavaneras and David Bestúe at Centro del Carmen in Valencia in 2019, JUMPING AT GLEASONS with the Viennese artist Bernhard Rappold, 89CM UNDERGROUND with Kiko Pérez in 2022, ORNAMENTO Y DELITO conference and performance at the Sala de Anatomía of the Universidad Complutense de Madrid and installation at Künstlerhaus Bethanien with Pilar Soler Montes (2023) or the most recent, in November 2023, SELF SUPER & HART AND KIND FOR ERIBODI at Krinzinger Galerie. During 2024 Felipe Talo develops in three chapters the project curated by Pilar Soler Montes, CUERDA Y CORAZÓN, of which the first chapter ELOEM was inaugurated at NADIE NUNCA NUNCA NADA NO in January 2024.

From 2007 to 2009 he worked with Nuria Fuster and held various solo exhibitions such as Circuitos 2007, Generaciones 2008 and Explum 2008 and 2009. In 2008, together with Nuria Fuster, Antonio Lozano and Pablo Valbuena, he developed the project HAMBRE (HUNGER), which was awarded the Matadero Madrid Creation Grants in 2011 and went on to hold three editions.

He has held several solo exhibitions of which METEMPSICOSIS: WOMAN WITH BLUE BALL, in Blanco Projektraum Berlin 2013, LA LEYENDA NEGRA at Galería Alegría 2014, LOS EXTREMEÑOS Fundación Arranz-Bravo, Barcelona 2016, HIPNOSIS, Ribot Gallery (Milan) 2016, CONFESIONES DE UN AMANTE EXTREMO at Galería Alegría 2018 and BALLASTEXISTENZEN, Galería Picnic 2023.

He participates in different projects and group exhibitions such as Casa Leibniz 2015 (Alegría Gallery) in Madrid, Estampa 2015 (Alegría Gallery) , Cuestión de Fe/Cuestión de trozo, together with Lucía C. Pino, Martín Llavaneras and David Bestúe at Centro del Carmen in Valencia in 2019, JUMPING AT GLEASONS with the Viennese artist Bernhard Rappold, 89CM UNDERGROUND with Kiko Pérez in 2022, ORNAMENTO Y DELITO conference and performance at the Sala de Anatomía of the Universidad Complutense de Madrid and installation at Künstlerhaus Bethanien with Pilar Soler Montes (2023) or the most recent, in November 2023, SELF SUPER & HART AND KIND FOR ERIBODI at Krinzinger Galerie. During 2024 Felipe Talo develops in three chapters the project curated by Pilar Soler Montes, CUERDA Y CORAZÓN, of which the first chapter ELOEM was inaugurated at NADIE NUNCA NUNCA NADA NO in January 2024.

©2024 Picnic by Una Agencia Más | Todos los derechos reservados | Aviso legal | Política de privacidad | Política de cookies